Over the past 13 weeks, in EDUC362 we have explored and learnt about an abundance of emerging technologies. We have investigated their uses and discovered how these devices can be powerful platforms in inspiring students’ creativity. After a long semester, the topic of constructionism perfectly sums up the work we have delved into throughout the unit. It emphasises design, collaboration, open ended-tasks, authenticity and most importantly, creativity.

So, what is Constructionism?

Constructionism is an educational theory devised by Seymour Papert that describes learning as an instantaneous result of active participation and knowledge construction. Papert suggests that students learn more when they are actively involved rather than gathering information via teacher directed discussions (Martinez & Stager, 2014). Constructionism emphasises engagement with phenomena and real-world problems and encourages students to develop and represent their understanding through physical design (Bevan, 2017). Therefore, technologies like virtual and augmented reality, 3D printing and game design are all excellent domains to demonstrate understanding and knowledge construction. However, constructionism doesn’t have to be isolated to just digital technology, constructionism can be implemented in all areas of the classroom online and offline.

Likewise, the Maker Movement emphasises open exploration through hands-on tasks where students can explore their own creativity and imagination freely (Bevan, 2017). As a result of these theories, schools are beginning to introduce design and technology spaces known as a ‘Maker Space’. These spaces are creatively furnished and thoughtfully equipped with resources and digital tools, to foster collaboration and creativity (Oliver, 2016).

So what might you find in a Maker Space?

Anything!

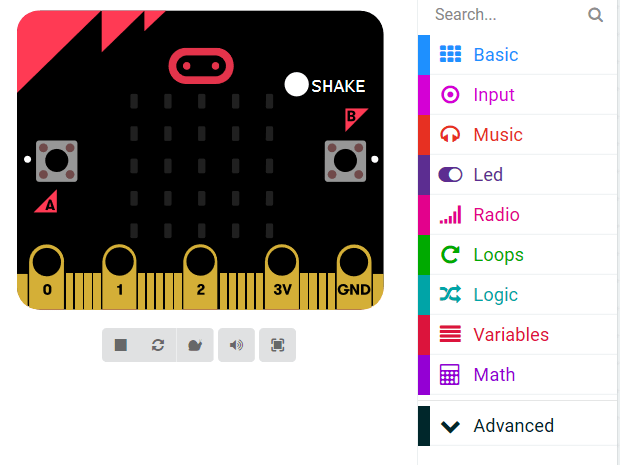

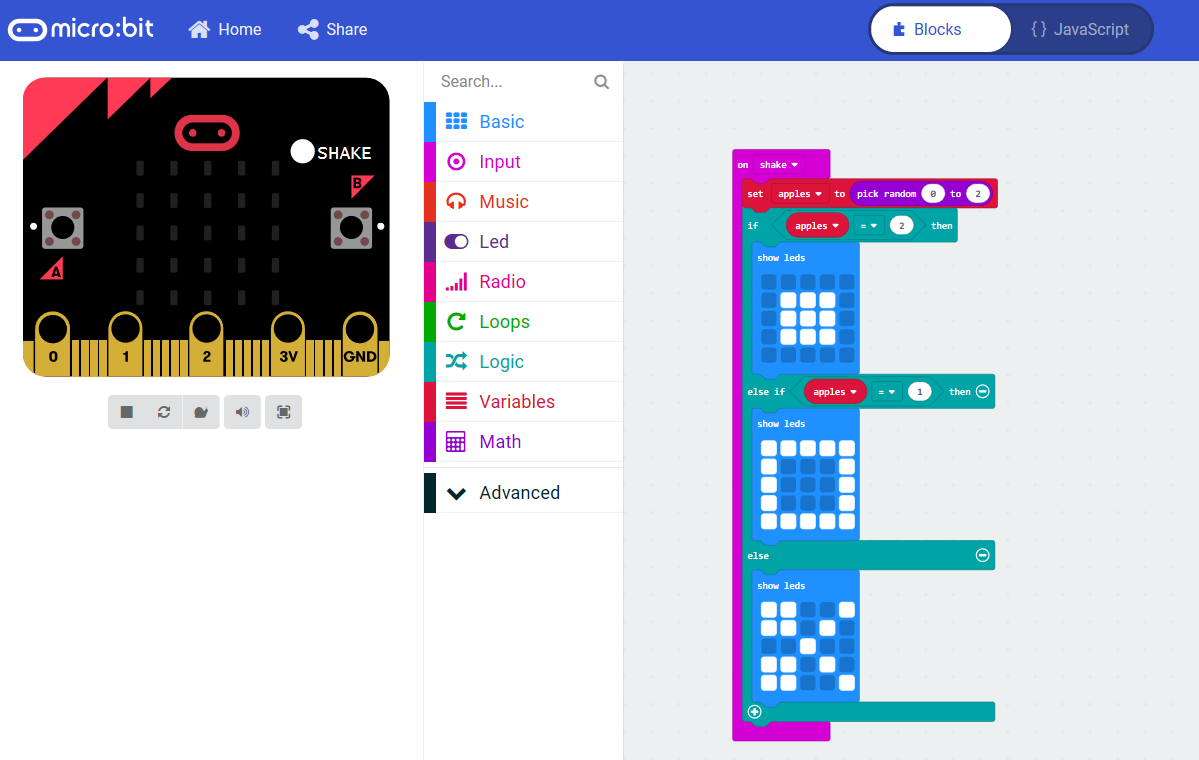

Cardboard boxes, 3D printers, building blocks, Microbits, robots, iPads, laptops… the possibilities are endless!

Some resources we explored in class, that would be great for a Maker Space include:

Makey Makey

- To learn about the transference of energy.

Turing Tumble

- To learn about computer science.

Little Bits

- To learn about circuits.

Additionally, a collection of problem-solving tasks could be beneficial! For example, in class we were given a collection of clues, a handful of nails and a block… Somehow, we were expected to balance 6 nails on just one upright nail… it was extremely difficult! But we got there!

Ultimately, a challenge like this would be a huge hit for students of any age to undertake as it encourages them to think outside the box and work as a team!

References

Bevan, B. (2017). The Promise and the Promises of Making in Science Education. Studies in Science Education, 53(1), 75-103

Martinez, S., & Stager, G. (2014). The maker movement: A learning revolution. International Society for Technology in Education. Available at: https://www.iste.org/explore/articleDetail?articleid=106

Oliver, K. M. (2016). Professional development considerations for makerspace leaders, part one: Addressing “what?” and “why?”. TechTrends, 60(2), 160-166.